Nie napisałem felietonu od dłuższego czasu, ponieważ razem z moją żoną Lindą wyruszyliśmy w rejs. Polecieliśmy do Grecji – do Aten, a stamtąd popłynęliśmy na Kretę, do Rodos i Turcji oraz z powrotem do Aten. To był dobry rejs. Statek był przepiękny, pogoda wspaniała, rozrywka znakomita, a posiłki na statku smakowite. Przytyłem dziesięć funtów!

Ale ostatecznie tym, co najbardziej mnie uderzyło w tym rejsie, były ruiny starożytnych cywilizacji, wśród których nagle się znalazłem. W Atenach zwiedziliśmy Akropol, zbudowany w okresie, który nazywano Złotym Wiekiem Grecji. Na wyspie Mykonos z przyjemnością zwiedzaliśmy wiatraki zbudowane 500 lat temu. Na Rodos zwiedziliśmy Pałac Wielkiego Mistrza Zakonu Rycerzy Rodos. Na Krecie zwiedziliśmy Pałac w Knossos, zbudowany 4000 lat temu. W Turcji spędziliśmy dzień w Efezie, spacerując po ruinach Świątyni Artemidy, jednego z Siedmiu Cudów Starożytnego Świata.

W każdym z tych miejsc słyszeliśmy o wojnach, które spustoszyły te niesamowite miejsca.

Widzieliśmy pałace, miasta, domy i farmy, o które toczyły się walki przez tysiące lat. Widzieliśmy ruiny, o które walczyli Ateńczycy, Spartanie i chrześcijańscy krzyżowcy, o które walczyli mieszkańcy Cesarstwa Rzymskiego, Perskiego, Bizantyjskiego, Osmańskiego i Rosyjskiego, a – ostatnio – o które walczyły Wielka Brytania, Francja, Niemcy, Włochy i Bułgaria.

Wszystkie te ruiny i opowieści o wojnach, które przetaczały się przez ten region niczym straszliwe, niekończące się burze, sprawiły, że zadałem sobie pytanie: „Czego tak naprawdę uczy nas cała ta historia?”

Jeśli spojrzysz do podręczników historii, sugerują one kilka odpowiedzi. Po pierwsze, powiedzą ci, że historia uczy nas cyklicznej natury cywilizacji. Imperia powstają i upadają, miasta rozkwitają i upadają, jedna kultura ustępuje miejsca innej. Po drugie, historycy powiedzą, że coś takiego jak pełna wojen historia regionu greckiego uczy nas, że ludzki duch jest nieugięty. Miasto zostaje zniszczone, a na jego miejscu powstaje inne, lepsze. Po trzecie, podręczniki historii sugerują, że istnieją „kluczowe lekcje”, których powinniśmy się nauczyć z przeszłości. Powstanie i upadek imperiów, starcia kulturowe i religijne oraz walki o władzę powinny dać nam wgląd w niebezpieczeństwa płynące z niekontrolowanej ambicji, nietolerancji i nienawiści do innych kultur, ras, religii i grup etnicznych.

Historycy twierdzą, że zrozumienie błędów przeszłości może poprowadzić nas ku bardziej pokojowej i sprawiedliwej przyszłości, przypominając nam o konieczności uczenia się na ofiarach i zmaganiach tych, którzy żyli przed nami.

A co myślę o tym wszystkim, co mówią historycy na temat tego, czego naprawdę uczy nas historia?

Myślę, że historycy mają w sobie tyle optymizmu, że ja kręcę głową z niedowierzaniem i zadaję sobie pytanie: „Czy ci historycy naprawdę studiowali historię?”. Czy czytali o wojnach w Europie Wschodniej i na Bliskim Wschodzie, które wciąż się powtarzają? Czy studiowali ludobójstwa, które wciąż się zdarzają? Czy nie słyszeli, że od czasów Holokaustu zginęło więcej ludzi w wyniku ludobójstwa niż w samym Holokauście? Czy ci historycy przechadzali się po niedawnych ruinach w miejscach, gdzie obecnie toczą się wojny, takich jak Ukraina, Izrael, Palestyna, Birma, Sudan, Etiopia, Syria, Jemen, Nigeria i Mali?

Podróż do Grecji i Turcji i poznawanie tysiącleci przemocy, chaosu i wojen uświadamia mi, że historia niczego nas nie uczy.

Jak mawiał mój ojciec – człowiek, który spędził 5 lat w obozie koncentracyjnym: „Wojna nie ma początku ani końca”.

Żadna historia, żadna religia, żaden rząd, żaden przywódca, żadna filozofia nigdy nas nie nauczy, jak położyć kres wojnie.

What History Teaches Us

I haven’t written a column for a while because my wife Linda and I were off on a cruise. We flew into Athens, Greece, and then sailed from there to Crete and Rhodes and Turkey and back to Athens. It was a great cruise. The ship was gorgeous, the weather superb, the entertainment outstanding, and the meals on the ship excellent. I gained ten pounds!

But finally what hit me the most about the cruise were the ruins of the ancient civilizations I suddenly found myself walking through. In Athens, we toured the Acropolis, built during what they call the Golden Age of Greece. On the island of Mykonos, we enjoyed exploring the windmills built 500 years ago. In Rhodes, we visited the Palace of the Grand Master of the Knights of Rhodes. In Crete, we visited the Palace of Knossos built 4000 years ago. In Turkey, we spent the day in Ephesus walking through the ruins of the Temple of Artemis, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

And in all these places we heard about the wars that ravaged these amazing sites.

We saw palaces and cities and homes and farms that were fought over for thousands of years. We saw ruins fought over by Athenians and Spartans and Christian crusaders, fought over by people from the Roman Empire and the Persian Empire and the Byzantine Empire and the Ottoman Empire and the Russian Empire, and – most recently – fought over by the United Kingdom and France and Germany and Italy and Bulgaria.

All of these ruins and talk about wars that rolled like terrible never-ending storms across this region left me asking, “What does all this history truly teach us?”

If you look at the history books, they’ll suggest some answers. First, they’ll tell you that history teaches us the cyclical nature of civilizations. Empires rise and fall, cities flourish and crumble, one culture gives way to another. Second, historians will suggest that something like the war-filled history of the Greek region teaches us that the human spirit is unyielding. A city is destroyed, and another, better one is built in its place. Third, history books suggest that there are “crucial lessons” we should learn from the past. The rise and fall of empires, the clashes over cultures and religions, and the struggles for power should give us insight into the dangers of unchecked ambition, intolerance, and the hatred for other cultures, races, religions, and ethnic groups.

Supposedly, according to these historians, understanding these past errors can guide us toward more peaceful and equitable futures, reminding us to learn from the sacrifices and struggles of those who came before.

And what do I think of all these things the historians say about what history truly teaches us?

I think the historians have an optimism that makes me shake my head in wonder and ask myself, “Have these historians really studied history?” Have they read about the wars in Eastern Europe and the Near East that continue to happen over and over? Have they studied the genocides that keep occurring? Haven’t they heard that more people have died of genocide since the Holocaust than died in the Holocaust? Have these historians walked through the recent ruins in places where wars are currently being fought, places like Ukraine, Israel, Palestine, Myanmar, The Sudan, Ethiopia, Syria, Yemen, Nigeria, and Mali?

Going to Greece and Turkey and learning about the millenniums of violence and chaos and wars tells me that history teaches us nothing.

As my father – a man who spent 5 years in a concentration camp – used to say, “War has no beginning and no end.”

No history, no religion, no government, no leader, no philosophy will ever teach us how to end war.

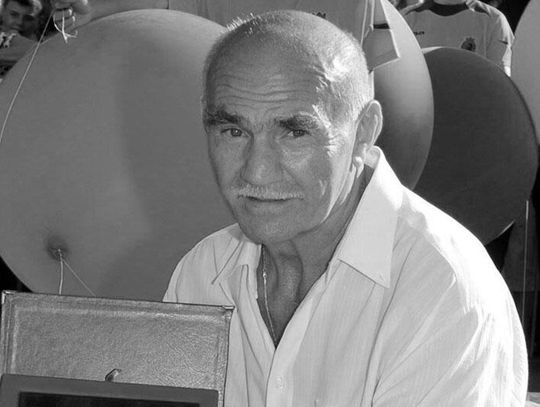

John Guzlowski

.JPG)

amerykański pisarz i poeta polskiego pochodzenia. Publikował w wielu pismach literackich, zarówno w USA, jak i za granicą, m.in. w „Writer’s Almanac”, „Akcent”, „Ontario Review” i „North American Review”. Jego wiersze i eseje opisujące przeżycia jego rodziców – robotników przymusowych w nazistowskich Niemczech oraz uchodźców wojennych, którzy emigrowali do Chicago – ukazały się we wspomnieniowym tomie pt. „Echoes of Tattered Tongues”. W 2017 roku książka ta zdobyła nagrodę poetycką im. Benjamina Franklina oraz nagrodę literacką Erica Hoffera za najbardziej prowokującą do myślenia książkę roku. Jest również autorem serii powieści kryminalnych o Hanku i Marvinie, których akcja toczy się w Chicago oraz powieści wojennej pt. „Retreat— A Love Story”. John Guzlowski jest emerytowanym profesorem Eastern Illinois University.

-

John Guzlowski's writing has been featured in Garrison Keillor’s Writer’s Almanac, Akcent, Ontario Review, North American Review, and other journals here and abroad. His poems and personal essays about his Polish parents’ experiences as slave laborers in Nazi Germany and refugees in Chicago appear in his memoir Echoes of Tattered Tongues. Echoes received the 2017 Benjamin Franklin Poetry Award and the Eric Hoffer Foundation's Montaigne Award for most thought-provoking book of the year. He is also the author of two Hank Purcell mysteries and the war novel Road of Bones. Guzlowski is a Professor Emeritus at Eastern Illinois University.